The diaries and journals of William Wilberforce were composed over more than half a century, from the year of his graduation from Cambridge University (1779) to the year of his death (1833). His earliest surviving diary was a travel journal written when he was turning twenty and recording his journey from Cambridge to the Lake District. No diary survives for 1780-82 during Wilberforce’s early years as an MP, but thereafter journals of some kind or another survive for the fifty years between 1783 and 1833. Some years are sparsely documented (1787, 1792, 1805-7, 1822), while the record is complete or almost complete for many other years.

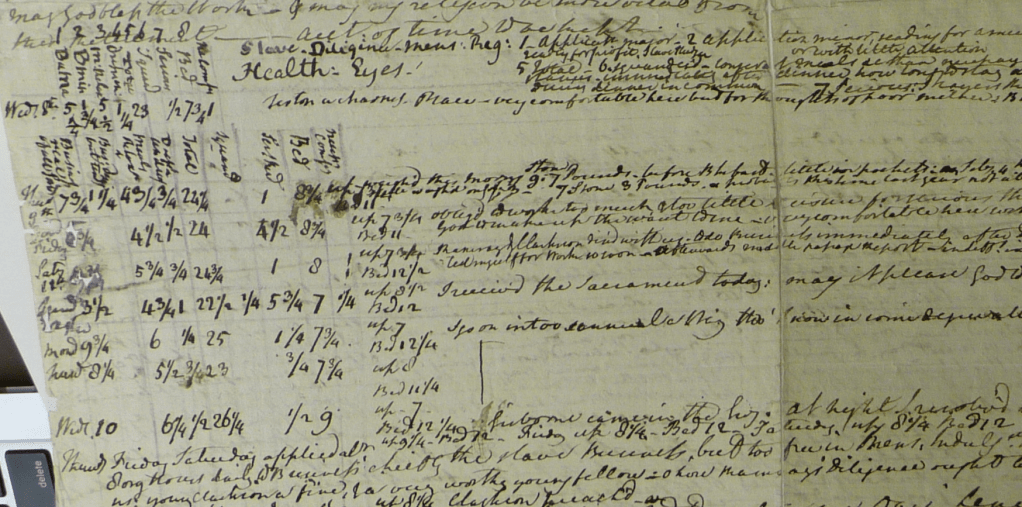

The diaries are remarkably various. The entries for 1783-86 were kept on a tiny notebook; between 1788 and 1791 Wilberforce wrote on large leaves of paper; from 1793 to 1800 he used a soft bound volume of 184 pages. The largest single volume (for 1814-22) was hard bound and contains over 160,000 words. Within the genre of the diary, we find sub-genres: the travel journal, the spiritual journal, the social diary, the parliamentary diary, the reading journal, the health and self-management diary. Between 1785 and 1811, for instance, Wilberforce maintained (somewhat sporadically) a religious journal. In the 1790s, he created tables to record his use of time. During this period and later, though not consistently, he made lists of his current reading. Entries for a single day can shift disconcertingly from parliamentary debates and imperial affairs to comments on sleep, food, bowel complaints, family or religion.

There is much in the diaries that is personal, sometimes painfully so. Robert and Samuel Wilberforce tell us that their father’s diaries ‘of earlier date bear upon them an order for their own destruction, which it was only within the last years of his life that he so far recalled as to desire them to be submitted with his other papers to the judgment of his nearest relatives’ (Life, I. vi). In his will, he bequeathed these papers to his second son, the Reverend Robert Wilberforce, and it seems to have been Robert who systematically worked his way through the manuscripts, marking potential extracts in red pen or in pencil. In their official Life of William Wilberforce, 5 vols (1838), Robert and Samuel published over 100,000 words from the diaries, along with generous extracts from the correspondence, supplemented by The Correspondence of William Wilberforce, 2 vols (1840). Subsequent biographers have mined these seven volumes and only rarely revisited the manuscript diaries. For a century and a half, most of the diaries were in the hands of the Wilberforce family, though access was granted to a few scholars (Reginald Coupland, David Newsome, Robin Furneaux, David Brion Davis). One volume (for 1814-22) was acquired by Wilberforce House Museum in the early twentieth century, and extensively employed by the biographer John Pollock. But even after the rest of the diaries were deposited in the Bodleian in the 1980s, and microfilmed, they were rarely used. Their sheer scale combined with the difficulty of Wilberforce’s handwriting deterred the great majority of readers. Biographers and historians continued to rely on extracts from the authorised biography.

This reliance on the Wilberforce sons is unfortunate, because while they did not fabricate material, they were highly selective. They wrote for the ‘public good’, seeking to present their father as one of the rare ‘examples to mankind’ (Life, I. vii). William Wordsworth complained that theirs was an exercise in ‘Idolatrous biography’. They also selected extracts that fitted with their own high Church, high Tory principles. In this sense, Wilberforce was a son of the Victorians, as well as a father of the Victorians. As one reviewer noted, ‘He who reads this book will know Mr Wilberforce, but he will know his sons better’. The material the sons omitted is often as interesting as the material they printed: details about their father’s inner struggles with sexual and other temptations; medical information, documenting his lifelong use of opium for pain relief; the names of specific individuals, anonymised to spare their blushes; family troubles, such as the bullying of younger brothers by William Wilberforce Jr. The sons systematically downplayed Wilberforce’s connections to religious Dissenters, and sought to obscure the importance of Thomas Clarkson to British abolitionism – thus provoking a public dispute with the veteran abolitionist that ended with a partial apology from Robert and Samuel.

The proposed edition, under contract with Oxford University Press, aims to present the complete, unexpurgated text of the extant diaries for the first time, a text of c. 950,000 words. Defining the diary as a series of dated entries by an individual recording their own life, and recognising the fluidity of the genre, this edition will publish what the sons called the ‘Religious Journal’ alongside what they termed the ‘Diary’. The great majority of the text will be drawn directly from the original manuscripts in the Bodleian and Wilberforce House Museum. Where an original manuscript diary available to the Wilberforce sons is no longer extant, we will reproduce the extracts published in the official Life (c. 30,000 words). The scholarly apparatus will include annotations identifying specific persons, places, events, books and correspondence; a general and textual introduction; appendices (e.g. of Wilberforce’s reading); and comprehensive indexes.

The Missing Diaries

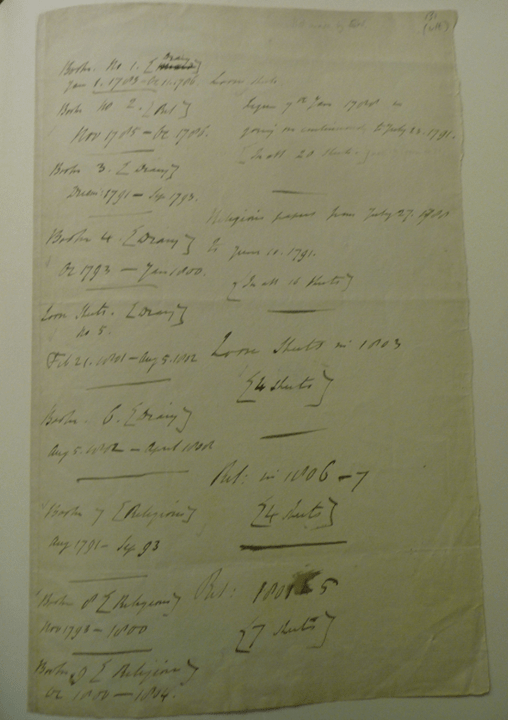

Some of the diaries and journals available to Robert Wilberforce in the 1830s are no longer extant. Extracts were included in the 1838 Life of William Wilberforce, but the original manuscripts are not known to exist either in libraries or in private hands. Robert made a list of the ‘books’ and ‘loose sheets’ available to him (see below).

Bodleian, MS. Wilberforce c. 39, f. 131. Courtesy of the Bodleian Library).

The most significant missing volumes are: ‘Book No 2 [Rel] – Nov 1785 – Oc 1786‘, the religious journal kept by Wilberforce in the year following his evangelical conversion; ‘Book 3 [Diary] – Decemb: 1791 – Sept 1793’ covering a critical year in the history of abolitionism; and ‘Book 6 [Diary] – Aug 5 1802 – April 1808’, covering the years leading up to the abolition of the British Atlantic slave trade in 1807. (We do have some manuscript diaries for 1802-4 but not for 1805-7).

What happened to these books? Robert may have destroyed them, either following his father’s instructions (if they ‘bore an order for their own destruction’) or because the controversy with Thomas Clarkson following the publication of the Life made the Wilberforce sons nervous about incriminating material in the manuscripts that contradicted their own version of events. Yet Robert preserved many other papers which contain embarrassing details, so these manuscripts may simply have become detached from the rest of the diaries and subsequently lost.