- Abolition

- Animals pt 1: Horses

- Animals pt 2: Animals at Home

- Correspondence

- Family Life

- Health

- Potatoes

- Reading

- Religious Conversion

Abolition

William Wilberforce is most famous as an abolitionist. For thirty-five years after 1787 he was the parliamentary leader of the campaign to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. The diaries provide an unparalleled record of his networks and they are especially rich for the second half of his career (after the passing of the Abolition Act in 1807). But as personal diaries and journals, the texts are often focussed on Wilberforce’s inner life, his domestic life, and his social life. By contrast, his references to political business can be laconic and cryptic; to gain a fuller understanding of his abolitionism, one must examine his speeches and correspondence. An additional frustration is that key periods of the campaign to abolish the slave trade are not covered in the surviving manuscripts, namely the months in which he first became involved in autumn 1786 to spring 1787, the high tide of popular abolition in 1792, and the final years of the anti-slave trade campaign 1804-1807.

The first mention of slavery-related topics in the diary is 13 November 1783, when Wilberforce wrote: ‘supp’d at Goostree’s – Edwards – Ramsay – Negroes’, presumably indicating a conversation about Revd. James Ramsay, the author of numerous abolitionist pamphlets throughout the 1780s (in the Life it is suggested that Wilberforce met Ramsay on this occasion, but this is unclear from the diary entry). The next mention, in late January 1788, is of conversations about the slave trade at dinner at Braithwaite’s on two consecutive days. By this time, Wilberforce is already committed to abolition – the gap in the surviving manuscripts covers the whole period in which he was introduced to the nascent anti-slave trade campaign and agreed to lead the efforts in the House of Commons. During this time, Wilberforce was encouraged to do so by Sir Charles and Lady Middleton, and by Thomas Clarkson. Wilberforce reflected on the events of his time in an autobiographical memo he dictated and in conversations with his friends and family. Thomas Clarkson and Charles Ignatius Latrobe, a Moravian Clergyman who was friends with the Middletons, both published their recollections of the period, offering narratives that Robert and Samuel rejected in the Life.

The entries surrounding the almost annual speeches and associated motions on the slave trade, 1789-1807, tend to pass comment on how well he performed, rather than a reflection on the campaign more broadly. In 1796, Wilberforce expressed surprise that the motion to bring in a bill for abolition was successful, and the document was not ready for a few weeks, having not been written in advance. In 1799, he mentioned a sense of hopelessness about the planned motion; this was reflected in the speech he made, rather than being confined to his diary.

The diaries demonstrate the range of abolitionist activity that Wilberforce was involved in after 1807 – lobbying government ministers and foreign visitors, reading papers, writing publications, planning motions and other activity – but also the range of other interests that took up similar amounts of his time. In the latter half of the 1810s, he begins expressing anxieties about having not done more to reform slavery, up to and beyond the tentative beginning of parliamentary action aimed at amelioration and emancipation in 1818. They also indicate that Wilberforce was less involved in the Antislavery Society than he was in the African Institution, correlating with his declining health and retirement from public life.

While Wilberforce main contributions to the abolition campaigns were in the House of Commons, it is the popular campaign that has attracted the most attention from historians, as the first major lobbying campaign of its kind. The diary does not offer many hints as to how Wilberforce viewed this during the peak of the popular anti-slave trade campaign, 1787-1792, but in the early years of the amelioration and anti-slavery campaigns commented that popular support needed to be mobilised.

The last mention of abolition-related business is on the penultimate page of the diaries. On 12 April 1833, Lord Barham took Wilberforce to an Antislavery Society meeting in Maidstone, at which the resolutions recently passed by the London Antislavery Society were adopted (to petition parliament for total, immediate, emancipation). Although he may have spoken at the meeting, Wilberforce made no comment about the content of the resolutions, noting instead that there were more Dissenting than Anglican ministers present, and that this had upset Mrs Robt and Frank Noel.

In later years there are some more reflective entries and glimpses into the decision-making process, but the diaries alone do not alter our understanding of Wilberforce’s abolitionism; he wrote about these matters at more length in correspondence, and in the various pamphlets he published throughout his career, as well as speeches in the House of Commons and at Anti-Slavery Society Meetings. ANNA HARRINGTON.

Animals, part 1: Horses

Horses feature frequently in Wilberforce’s diaries. As the primary mode of transport at the time, horses were ubiquitous in daily life (it is estimated that c.1800 there were 31,000 horses in London, see Almeroth-Williams, City of Beasts). Wilberforce regularly mentions travel arrangements; the use, condition, and price of post-horses; and accidents involving horses and/or carriages. However, as well as a routine part of Wilberforce’s life, some mentions of horses are markers of changes in Wilberforce’s life, which will be explored here.

The 2006 bio-pic, Amazing Grace, opens with Wilberforce coming across two men beating a horse. Wilberforce intervenes and the men stop when they find out who he is. There is no indication in the diaries, or in Wilberforce’s correspondence, that such an event took place. The fictional incident was probably meant either to display Wilberforce’s reputation, or as a nod to his future involvement in the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (which will be discussed in more depth in pt. II).

As a sociable young man before his evangelical conversion, Wilberforce attends horse races. In August 1783 he mentions that his horse won at Harrogate, although whether that is a horse he owned or the horse he placed a bet on is unclear. After his conversion, he came to reject both gambling and attending the races. When his eldest son, William, was away at school in 1811, Wilberforce’s friends convinced him not to send a pony for him to ride there, to prevent ‘making him too fond of riding dangers … Racing, Hunting &c’ (25 April 1811). He had wanted to send a horse so that William would be confident on horseback, a key skill not only for transport but for socialising (see Almeroth-Williams, City of Beasts) outside of the pursuits that Wilberforce avoided. His sons often travelled on horseback when visiting Wilberforce from school or university, or alongside the carriage on family holidays.

During his major illness in 1788, he was too unwell to ride on horseback – in May of that year, he ‘mounted horse for first time there (I know not how many) months’ (7 May 1788). Before 1788, he appears to have regularly travelled on horseback, especially in the Lake District or within London. After his illness, his time on horseback decreased, with a few exceptions. He continued to ride on horseback on election days in York, where he would ride up to the castle after his re-election was confirmed (7 April 1784; 12 July 1802). In June 1811, he ‘mounted poney’ to see a friend’s new farm (3 June 1811), and in 1815 he explored the grounds of Clovelly Court, in Devon, on a pony while his sons were on foot (11 August 1815). The last occasion on which Wilberforce was definitely on horseback rather than in a carriage or ‘poney chair’ was in 1831, when he rode his daughter-in-law’s pony on Brixton Down (3 September 1831). The limited time on horseback from the 1790s onwards suggests that Wilberforce’s health problems made riding uncomfortable, but that on some occasions, over long distances, his physical frailty made it a better choice than walking.

Of course, no mode of transport is risk-free. In 1816, Wilberforce was advised to keep William’s horse ‘which safe enough if He takes Care,’ a comment which implies there had been an accident, or a near-accident, although the diary does not include any additional details (3 April 1816). As well as possible horseback accidents, carriage accidents were common. After travelling a total of over 800 miles in November 1816, he wrote ‘what a call for thankfulness, not a single accident’ (29 Nov 1816). In 1814, Wilberforce was travelling between events in London with Lord Redesdale when the carriage ran over someone. Redesdale gave his name but didn’t stop, which Wilberforce felt they ought to have done (14 May 1814).

In Wilberforce’s diaries, horses are both a constant presence and an indication of life circumstances. As a young man, they were a part of elements of his social life that he later rejected; as someone with health issues, horseback riding was both a problem and a solution. ANNA HARRINGTON

Animals, part 2: Animals at Home

Horses, as discussed in Animals, part 1, were a frequent feature of Wilberforce’s daily life. Other animals were present but less prominent, and Animals, part 2 will focus on ‘household’ animals.

Other than a single mention of being disturbed at night by ‘Dog barking’ (24 August 1826), dogs only feature in Wilberforce’s diaries when he has, or hears about, encounters with dogs suspected or confirmed to be rabid (e.g. 21 September 1809, 8 October 1809, 22 July 1824, 30 August 1825). In parliament, he supported the introduction of a Dog Tax in 1796, partly in response to an outbreak of rabies. Wilberforce argued that it would a humane measure because it would discourage people from keeping dogs that they could not afford as well as protecting ‘the lower orders of society’ from rabid dogs and the potential transfer of rabies to humans (speech in House of Commons, 5 April 1796).

Samuel Wilberforce wrote to his father from Oxford in 1823, asking ‘Do you dislike my having the dog I have here?’, an opinion he had recently heard Rev. Spragg (his former schoolmaster). He suggested in his letter that if Wilberforce did disapprove of Samuel’s canine companion he would ‘take some means of disposing of it’ (Bodleian, 21 June 1823). Unfortunately, Wilberforce’s reply to Samuel’s query has apparently not survived, so we do not know the final fate of the dog. Given the opinion he expressed thirty years earlier about the cost of keeping a dog, and his increasing financial anxiety, he may have been against Samuel keeping a dog while at Oriel College for practical reasons.

Samuel mentioned that Wilberforce must have known he had the dog in question, as it had been at Marden Park with him on his most recent visit. Wilberforce’s apparent ignorance of the dog suggests that there may have been other dogs present in the household, but he doesn’t mention any dogs at home in the diary. This could be because the dogs were not seen as something to comment on – as common as horses, perhaps, but with less impact on Wilberforce’s daily life. There are references to ‘hounds’ in the diary, but largely in the context of hunting, and these will be discussed in a third entry on animals, focused on animals “at work” (coming soon).

While dogs in domestic settings were increasingly common during Wilberforce’s lifetime (see Blaisdell, ‘The Rise of Man’s Best Friend’ on the evidence shown by the 1796 dog tax), Wilberforce’s household could also contain more exotic animals. In 1812, he was given an antelope as a gift. The antelope’s arrival and departure at Kensington Gore are the full extent of what the diary informs us, but the sons include the antelope in the Life, quoting from Wilberforce’s correspondence to add detail. They do not, however, add anything substantial beyond what is quoted. When it first arrived in Britain in October 1812, he was away from home and there were few servants at Kensington Gore to care for it, so Zachary Macaulay took custody of the creature (Life 4:74). The antelope arrived at Kensington Gore on 11 November 1812, where it remained for a little under a month until the ‘Duchess of York last week took my Antelope’ (15 December 1812). The Duchess of York had a menagerie at her primary residence at Oatlands Park, in Surrey. When the antelope first arrived in London, Wilberforce wrote that he hoped it would not ‘molest the residents’ at Macaulay’s and although in a following letter the postscript declares that ‘My little girls are in love with the antelope from Matthew’s description’ (Life 4:79-80), it was probably not suited to London life.

While antelopes and dogs were not guaranteed a long-term welcome to Wilberforce’s home, he was very happy for Marianne Francis (see Women, part 2), to bring her ‘tame Hare’ with her on a visit in 1815. When she wrote to make the request, he replied ‘if Love me love my dog is an established axiom, much more Love me Love my Hare holds true in this House, where among some of us Dogs have not their due Estimation’ (Pollock, ch. 21). The visiting hare doesn’t feature in the diaries, but the anecdote does fit within the bigger picture of Wilberforce’s relationship with animals. He had paraphrased the same axiom in 1812 when writing to Macaulay about the antelope. Wilberforce’s hospitality clearly extended beyond a house full of ‘Inmates’ (as he termed longer-term visitors) to include other people’s pets. ANNA HARRINGTON

Correspondence

Throughout the diaries, Wilberforce complains of the amount of time taken up by his correspondence. In the summers, he travelled with his ‘arrears’ – the letters that had built up, unread and unanswered – in the hope of clearing the backlog. Even after his retirement, when correspondence ceased to be a part of his role as MP, he mentions the volumes of letters. In addition to letters relating parliamentary business and Wilberforce’s various other interests, e.g. missionary work, there are many personal letters. With friends he shared news about himself, his family, and mutual acquaintances. He also wrote to his children, offering advice about use of time and religious matters, as well as news from home.

As an MP, Wilberforce had franking privileges, meaning his post was free of charge and thus enabling him to continue extensive correspondence at no expense to himself. Sometimes he posted letters for others: in October 1791, after visiting the rectory of Dorothy Wordsworth’s uncle, William Cookson, he posted a letter from her to a friend bearing the frank: ‘Thetford Octr tenth 1791 W free Wilberforce’. On retirement, his last frank was sent to his son, Robert, at Robert’s request. However, his correspondence with Thomas Fowell Buxton, the MP who took Wilberforce’s place as lead-abolitionist in parliament, indicates that Buxton effectively provided Wilberforce with franks by posting letters on his behalf, in 1827 and perhaps at other times. He had previously discussed the abuse of the franking system with Charles Sumner, the newly appointed Bishop of Llandaff, in August 1826 who, he wrote, was ‘very loose abt giving Franks ad libidum’.

While the diaries are all written in Wilberforce’s own hand, he employed an amanuensis for some of his letter writing, in order to prevent straining his eyes more than necessary. He added personal postscripts to some of these dictated letters and tended to write the letters himself when he wished for the contents to remain private.

Some of his letters were collated by his sons as Correspondence of William Wilberforce (2 volumes, 1840), and a further selection were published as Private Papers of William Wilberforce (1897) by a descendent. Letters from Wilberforce are also included in edited volumes of his contemporaries’ correspondence or memoirs. Many more letters than have been published are available in archives: the largest collection is now held at the Bodleian Library, around 200 are held at Wilberforce House in Hull, and many are scattered in the papers of other people at the British Library or local record offices.

Alongside the transcription of the diaries, the Wilberforce Diaries Project is generating a calendar of Wilberforce’s correspondence, in hopes of being able to add information about the letters being sent and received in the final editions. ANNA HARRINGTON.

Family Life

Wilberforce married Barbara Spooner on 30 May 1797, and within the next ten years they had six children: William (1798), Barbara (1799), Elizabeth (known as Lizzy) (1801), Robert (1802), Samuel (1805) and Henry (1807). His diary offers glimpses into their family life, which took up an increasing amount of his attention over the years.

When the Wilberforce children were still at home, birthdays were typically holidays. On Robert’s ninth birthday, in December 1811, ‘after [dinner] Children had their play of king Queen &c as on a birthday in my Court dresses &c’ (19 December 1811), repeated a month later for Lizzy’s fourth birthday when ‘the Children mumming abt Lizzys Birthday in my dress clothes’ (20 January 1812). The next year, her birthday was marked with a trip ‘to see the great fish & Toyshops’ (20 January 1813). Less excitingly perhaps, on William and Barbara’s joint July birthday in 1809, after a trip to Beachy Head, Wilberforce noted praying with them (21 July 1809).

Several of these positive anecdotes, such as the birthday court-dress game, were included in the five-volume Life by his sons. What they did not include were the repeated moments throughout their lives that Wilberforce expressed concern about their characters, frequently lamenting their laziness, ill tempers, or lack of piety. Although this would not have made for especially edifying reading for them in the process of writing the biography, the complaints are unlikely to have been a surprise to them, as they also featured in the letters from their father while they were at school.

In 1811, when he contemplated leaving parliament, he listed ‘the state of my family’ (24 August 1811), especially his children’s moral education, as the chief reason in favour of doing so. The education of his sons was a topic of frequent discussion, particularly when time came for them to move between schools, tutors, and university. These discussions often included close friends like Babington, who argued in 1816 that William would be better off going away to school, while Wilberforce was in favour of engaging a private domestic tutor for him. When he received reports about his sons, who in the end were mostly educated away from home, he either expressed pleasure at the account given, or anxiety about their characters.

William Wilberforce jr., as Wilberforce’s heir, was a source of particular anxiety for his father. On at least two occasions (in January 1812 and March 1819) Wilberforce considered making his inheritance contingent on good behaviour.

Both of his daughters pre-deceased him. Barbara (noted by Wilberforce as ‘b’ in an echo of her mother’s typical ‘B’) died on 30 December 1821, and Lizzy in March 1823. They were both frequently unwell, and anxiety about their illnesses was a frequent feature of his diary. Wilberforce noted in November 1821, shortly before her death, that Barbara suffered from ‘my old complaint’, possibly a reference to his digestive issues. In both instances, the Life includes excerpts from letters reflecting on the sad occasion. ANNA HARRINGTON.

Health

Wilberforce’s continually included information about his own health, and the health of those around him, in his diaries and journals. He was generally known to be routinely unwell, due to a digestive complaint presumed to be a form of colitis, and from 1788 onwards was reliant on opium, sometimes in the form of laudanum and sometimes in pill form, to manage his symptoms. What follows is a short overview of how Wilberforce discussed his health and how this changed over the course of the fifty years of his diaries. It is by no means a complete analysis of the theme due to the volume of material that could be included.

The widespread awareness of his ill-health and opium dependence meant that his sons could not avoid mentioning both in the Life. His opium use was, however, limited to a single paragraph later in the biography, and his health overall was not as large a feature of the sons writing as it was a feature of Wilberforce’s daily life. In 1792, he wrote in his religious journal that ‘I mean to make my Health an object of great attention’. The attention paid to his health, which he commented on at least weekly, throughout his diaries, shows that he did so.

In 1788, shortly before Wilberforce was supposed to introduce the first motion against the slave trade in the House of Commons, he had his first major attack of presumed colitis. Apparently, he nearly died, and did not write in his diary for several weeks. He then spent several months in Bath and Cambridge to recuperate in peace before returning to London. This proved to be a watershed moment for his health both on and off the page. Prior to 1788, there are occasional mentions of stomach upsets, but most comments about his health refer to colds, hangovers, or, most commonly, his poor eyesight. Thereafter, Wilberforce was frequently unwell to a lesser or greater degree. His next near-fatal illness was not until 1823, when he had a serious bout of pneumonia, but he had regular periods during which his bowels were a major impediment to his daily life.

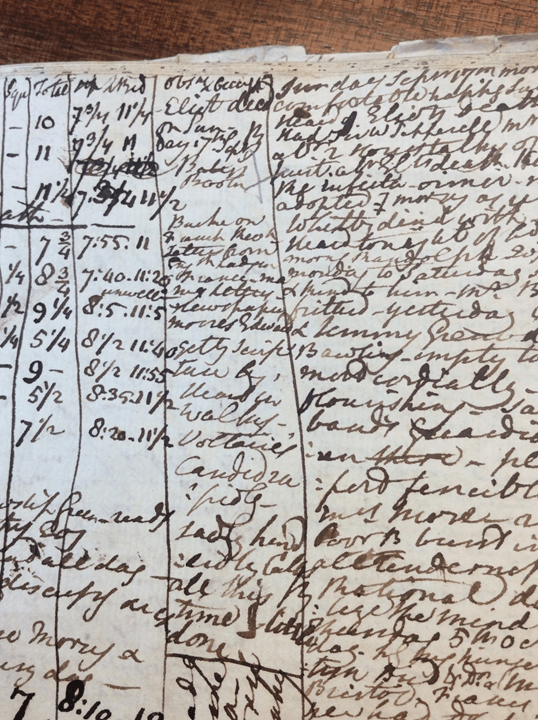

From 1788 onwards, his health is a constant thread throughout his diary. The state of his health was included in the tables he created in his diaries through the 1790s (continued from the 1780s), and he also wrote short recaps of his recent health from time to time. In the 1790s a couple of these included more detailed, and graphic, descriptions of his symptoms, which correspond with the symptoms for colitis listed by the NHS. Wilberforce’s management of his health – through daily walks, diet, attention to sleeping patterns, staying at home when there was a perceived risk, opium, and other treatments – is detailed throughout the diary. As well as his daily dosage of opium (which, contrary to the sons’ account as repeated by subsequent biographers, increased several times in addition to ad hoc higher doses), he also saw eye specialists several times for various treatments, and had his throat ‘Electrified’ in December 1811. When he decided to retire as MP for Yorkshire, his health was one of the reasons he listed. Similarly, when he retired from parliament altogether in 1825, it was in part because his physician had recommended that he attend the House of Commons so little, to preserve his health, that he would rarely be there.

Wilberforce used a range of words to describe illness. His short recaps of his recent bodily condition are often labelled ‘Health’ in the margins, and in passing he would refer generally to ‘my Health’. He described the problems with his digestion as his ‘bowel Complaint’ and used ‘Complaint’ similarly regarding his eyes and lungs, both of which were prone to serious issues. When his digestive issue was especially bad, he described it as an ‘attack’. Initially he would describe himself/his digestion/etc as ‘Indifferent’ to indicate feeling unwell; this later changed to ‘poorly’ as the most frequent adjective used regarding his health. Wilberforce described other people as ‘ill’ more than he described himself as such. Similarly, other people had sickness, or sickness was spreading around. ‘Unwell’ was infrequently used, and usually regarding his children or close friends. As well as these generic adjectives, he identified specific diseases – colds, influenza, measles, mumps, scarlet fever, gout – and some of the specific symptoms that family members experienced.

Diagnosing health issues in historical figures is not a simple task. The symptoms that Wilberforce described in his diaries and correspondence match the symptoms of forms of colitis (per the NHS website), and therefore it seems likely that his ‘complaint’ was along those lines, but should not be taken as a proven fact. ANNA HARRINGTON

[material for this entry was also presented at the BSECS 2023 conference in January 2023]

Potatoes

The humble potato may not seem like an important ‘theme’ in someone’s diaries, but the different contexts in which Wilberforce mentioned potatoes highlights the way in which his diaries feature both national, political concerns – in this case, food supplies – and domestic life – what is on his plate.

Wilberforce first mentioned potatoes on 16 March 1800, listing his occupation that Sunday as ‘Canals & other Business – Potatoes & Fish &c I much grieved at Pitt’s Languor about Scarcity.’ Low crop yields led to food shortages in 1799-1800, which in turn increased the cost of grain, threatening famine. This was worsened by a blockade by the Baltic powers, preventing grain imports. In response, the Board of Agriculture, of which Wilberforce was a member, published a Report on the High Price of Provisions in February 1801, suggesting that offering a bounty for potatoes might encourage more people to cultivate the vegetable. Wilberforce defended the recommendation in the House of Commons from opposition stemming from claims that government interference had led, and would lead, to further price increases, rather than increased supplies and price decreases (02 – 04 March 1801). He had previously engaged in an extended correspondence with Arthur Young, the agriculturalist, about potato yields and costs, actively taking an interest in the topic. In Wilberforce’s diaries, the days of the debates simply read ‘House – Potatoes’ (02 and 03 March 1801), while on 27 February, when the House was due to discuss the Report, he noted that ‘Poor Potatoe premiums ousted by sudden adjournment.’

He later commented on the success of the vegetable both as a trading commodity and as a crop, reflecting his parliamentary interest in the vegetable. In November 1810, he noted that ‘This man* gains a large fortune annually by potatoes for the London Market.’ Decades later, after late frosts in May 1831, he reported a ‘copious bloom on the Apples and Potatoes’ and ‘great injury to young Potatoes, Cherry Blossoms.’

Potatoes were also included in Wilberforce’s own diet. Most of his references to eating potatoes are within longer descriptions of his health: on 30 July 1808 he recorded that ‘I have been Extremely well, I eat a little Potatoe every day,’ whereas on 17 December 1809 he wrote ‘I suspect my Indisposition partly from Cold, partly Eating Potatoes yesterday not boiled enough.’ Within a two week period in August 1810, he had connected eating potatoes to an improvement in his digestion and had then lain awake wondering if he had eaten too many potatoes. He also reported eating a plate of cold ham and potatoes at a coffee shop before attending the House of Commons in February 1816 (the food plus a pint of wine cost 9s, with 1s for the waiter). The final mentions of Wilberforce eating potatoes are in November 1831, in a similar vein to those described above. The relatively casual manner of the inclusion of potatoes indicates that, although at times he viewed the food as a health concern, it was not a novelty in his life (potatoes had become an increasingly common feature of British diets over the previous century-and-a-half). ANNA HARRINGTON

*possibly Benjamin Flowers, the editor of the Cambridge Intelligencer, as the name most recently mentioned in the entry.

Reading

From 1788 onwards, Wilberforce employed his diaries to record his reading. Further evidence of his bookishness comes from his correspondence, speeches and writings, and the several hundred volumes of his library now held at Wilberforce House, Hull. Surprisingly, there has been no systematic analysis of Wilberforce as a reader, though his sons tell us that even in old age ‘his love of books was still extreme’. Europe’s leading female intellectual, Germaine de Stael, claimed after a number of conversations that he was ‘remarkably well-versed in everything pertaining to literature and that lofty philosophy based on religion’. Wilberforce spent much of his working life immersed in letters, newspapers and periodicals, but he also read a wide range of books, and the Diaries Project is currently cataloguing his reading. Often, he had books read to him, whether by servants (‘while dressing’), visitors (in the evening), or family members. When Parliament was not sitting, he used the time to read more intensively, either at home or on his travels (Bath, Yoxall Lodge in Staffordshire, and Weymouth were favourite vacation spots).

His reading was eclectic, mixing the sacred with the profane. In 1802, he was sampling ‘Gibbon’s Decline and Macartney’s China’ alongside ‘[Jonathan] Edwards On the Religious Affections – an excellent book’. A year later, he was combining ‘a little Hume’ and Adam Smith with the Greek New Testament. In October 1797 (see below), he was re-reading Burke on the French Revolution, while ‘getting Scripture by Heart in walking’, and perusing ‘Voltaire’s Candid[e] rapidly’.

He was well read in Enlightenment thought. Although familiar with Montesquieu, Voltaire and Rousseau, he spent much more time in the writings of the Scottish Enlightenment: Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations; David Hume’s Essays and his History of England; Adam Ferguson’s Roman History and his Essay on Civil Society; William Robertson’s histories of America, Charles V, and India; and works by James Beattie, Thomas Reid and Dugald Stewart. Among contemporary English thinkers, he read Edmund Burke, William Paley, Joseph Priestley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft on her travels in Scandinavia.

He was a keen reader of literary classics. The poet Horace was a favourite, and he enjoyed Shakespeare’s plays. He read Swift, Pope, Addison, and Johnson for ‘Relaxation’, though his favourite poet was the Whig evangelical William Cowper. Throughout his life, he read novels, though often with ambivalence. He complained about the lack of Christianity in English novelists like Sterne, Fielding and even Goldsmith, but he read novels for pleasure as well as to understand the zeitgeist. Walter Scott became a particular favourite.

On Sundays, Wilberforce would concentrate on ‘serious reading’, i.e. religious books. His religious conversion in 1785-6 had involved reading the Greek New Testament along with Philip Doddridge’s The Rise & Progress of Religion in the Soul (1745). In later years, he read many such works by authors like John Witherspoon, Jonathan Edwards, and his mentor, John Newton. He was also fond of seventeenth-century religious classics, by authors including the Scottish archbishop Robert Leighton and the English Puritan Richard Baxter. JOHN COFFEY.

Religious Conversion

What does the manuscript diary reveal about Wilberforce’s religious conversion, 1785–86? Ostensibly, not much. The text provides no meaningful comments on either his basic Christianity or his emerging Evangelicalism. So, at best, the diary would seem to give rise to a biographical narrative that helps to contextualise more pertinent details gleaned from other sources.

On further inspection, however, there are points of interest. During the summer and autumn of 1785, Wilberforce’s spiritual journeying was complemented by physical travelling. His excursion to the continent meandered around an irregular circle, thereby enacting a type of conversion. His body, mind and soul were made restless; and, coincidentally, so too were his bowels.

Some familiar experiences in pleasure and politics were observed to have merely moved to sunnier climes. In stopping off at Plombieres-les-Bains for fresh horses, Wilberforce noted that here Lord and Lady Maynard, as well as the Duke of Bedford, resided in ‘sweet retirement’: a suitable turn of phrase given their ménage à trois. One night at Lausanne, Wilberforce ‘staid late… with Lady Clarges’, a fashionable musician who had lost a husband only to gain a female companion turned lover. At Geneva the extra-parliamentary reformer Christopher Wyvill assuaged his disappointment at the failure of the Reform Bill by becoming engrossed in the constitution of that city. And, selected acquaintances revealed themselves to be of a ‘Pittite’ persuasion.

Yet, patterns in nature and faith became beautifully strange. Swiss mountains, the like of which Wilberforce had never seen, comprised a ‘heavenly view’. The pioneering scale models of these dominions by the cartographer Franz Pfyffer facilitated a navigation of and a meditation upon this ‘charming’ and ‘delightful’ landscape. Swiss alpine culture delivered Wilberforce from base indulgences and helped to elevate his spirit. At Zurich, an encounter with the mystical pastor Johann Kaspar Lavater proved formative. He ‘kiss’d’ Wilberforce and other members of his company “with extreme affection” and declared that ‘if he received anything’ then they ‘should too’. In this moment Wilberforce recognised that Lavater and others like him looked ‘for the coming of some Elu [elected soul?] who is to impart to them a larger Measure of Grace he will know the Elu the moment he sets Eyes on him’. Three years later, Lavater’s choicest manuscripts had been translated and published as Aphorisms of Man — a work that was read and annotated by a young William Blake.

The unfamiliar intermingled with the familiar; not as contrasting and newly antagonistic expressions of virtue and vice, but as two types of continency playing out in a life being lived. The world of the flesh did not suddenly become anathema to Wilberforce. That said, there was something of a moral turn. He lamented that men ‘do not see that their duties increase with their fortunes’. A reveller at White’s was judged to have been in ‘a wretched state’. Then whilst at Spa he noted with some indignation that is was ‘wrong to go to the play’.

Christian conversion narratives often found themselves utilizing the phenomenology and/or rhetoric of silence to craft a suitable medium through which to initiate the process of conversion. With this in mind, it is most curious to witness a silence of sorts in Wilberforce’s diary. Not a break in his writing, but rather a series of regular entries that say almost nothing. Having reached the enchanting town of Spa, Wilberforce checked into a hotel and initially proceeded as normal. Then from Friday 16 September to Friday 30 September he wrote a diary entry each and every day but only to comment on the inclement weather. It was as if he was communing with the brooding elements, meditating upon them as they reflected the conviction of his sin. Yet, a later entry on 20 October makes plain that Wilberforce had certainly spent a fair amount of his time at Spa in convivial engagements, eating, drinking and entertaining friends and acquaintances of social distinction. So, what was on his mind for those two weeks in late September and what did he do? Did the period mark some kind of crisis?

A few months later, once back in England, Wilberforce had cause to observe in his diary that the evangelical Church of England clergyman John Newton had the ‘Composure & happiness of a true Xtian’. Such discernment might be seen as a confirmatory act of Wilberforce’s own conversion. DAVID MANNING.